COMPETITION IN DIGITAL MARKETS

Australia’s ACCC taking on Google’s ad tech business

This article is a follow-up to “Showdown Down Under?” which was published here last year. As our cycle aims to explore jurisdictions outside the EU and North America, we will further dive into Australian competition law by outlining its basic structure, introducing the relevant actors and give an insight into the pursued policies in the realm of digital markets with a particular focus on “ad tech”.

Marco Schmidt

September 21, 2022

Australian Antitrust Laws

Australian antitrust law is governed by the Competition and Consumer Act of 2010 (CCA, former Trade Practices Act of 1974), mainly in its Part IV which deals with restrictive trade practices. Notably, since 2009, cartel conduct can constitute a criminal offense which will be severely punished, including prison sentences. Just recently, for the first time ever, an individual pleaded guilty to criminal cartel conduct. This is naturally accompanied by the common private procedures that can be brought against cartelists. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC, chairman until March 21, 2022: Rod Sims, then to be followed by Gina Cass-Gottlieb) is in charge of enforcing the CCA, therefore not only dealing with matters of antitrust law but also with consumer protection as the name already indicates. This gives the ACCC a wide range of competences which might make it an “economic super-regulator” in the eyes of some. Indeed, sector inquiries, like the 2019 Report on Digital Platforms, pave the way for further regulation like the News Media Bargaining Code, which triggered the conflict with Facebook/Google and the Australian government earlier in 2021 (c.f. “Showdown Down Under?”). In fact, the News Media Bargaining Code was even drafted by the ACCC. As the head-organization of the ACCC is the Australian Treasury (“the Australian Government’s pre-eminent economic adviser”), the strong influence of the ACCC on Australian legislation is caused by the way the authorities are structured and interlinked. At the same time, the ACCC’s competences are, of course, not limitless as the specialized “Australian Competition Tribunal” decides upon appeals against decisions of the ACCC, for example when a merger was prohibited.

Current focus

Unsurprisingly, and just like in many other jurisdictions, Australia will focus further on digital (platform) markets. With the News Media Bargaining Code the country was one of the first to seriously take on the players in Big Tech and the ACCC has no intention of losing its drive. ACCC Chairman Rod Sims considers ex ante regulation of digital platforms in a speech given in October 2021 and refers to all the other ongoing efforts with regards to updating antitrust legislation all around the world, such as the Digital Markets Act and Digital Services Act in Europe. One also needs to consider that regulation in Australia will not only focus on questions of competition but also on privacy and consumer data, especially since the ACCC is the authority responsible for consumer protection and competition at the same time. This development is also not new per se as, for example, the German Federal Cartel Office (Bundeskartellamt) has brought a case against Facebook considering questions of the protection of consumer’s data. It might raise some eyebrows though how influential the ACCC is in advocating for certain policy goals and, later on, drafting legislation. The ACCC pushes for more regulation and hence for more competences for itself, something that at least needs to be critically looked upon.

Ad Tech Inquiry

As outlined above, the ACCC has a strong focus on current digital developments and does not refrain from taking on the players in Big Tech like Facebook or Google. In September 2021, the ACCC fired again some serious shots against Google, by publishing its “Digital advertising services inquiry”. In that regard, digital advertising includes the usage of ad tech services which facilitate the buying, selling and delivering of digital display advertisement, meaning ads that are shown to consumers that visit a website or use an app. Publishers, in a digital context for example a platform like Facebook or Youtube, sell their advertising space (so-called ad inventory) to advertisers. The inquiry of the ACCC though did not focus on a closed display channel like Facebook that uses its own system to sell ads directly to advertisers but on display advertisement through open channels.

In open channels, publishers sell their inventory with the support of ad tech services. The report acknowledges the complexity of the ad tech supply chain which is why a closer look shall be taken at one specific concern: As outlined above, in the advertisement market, publishers and advertisers are the two counterparts to the transactions. While this is the only dimension in the case of closed channels, open channels are defined by the need for intermediaries to connect publishers and advertisers.

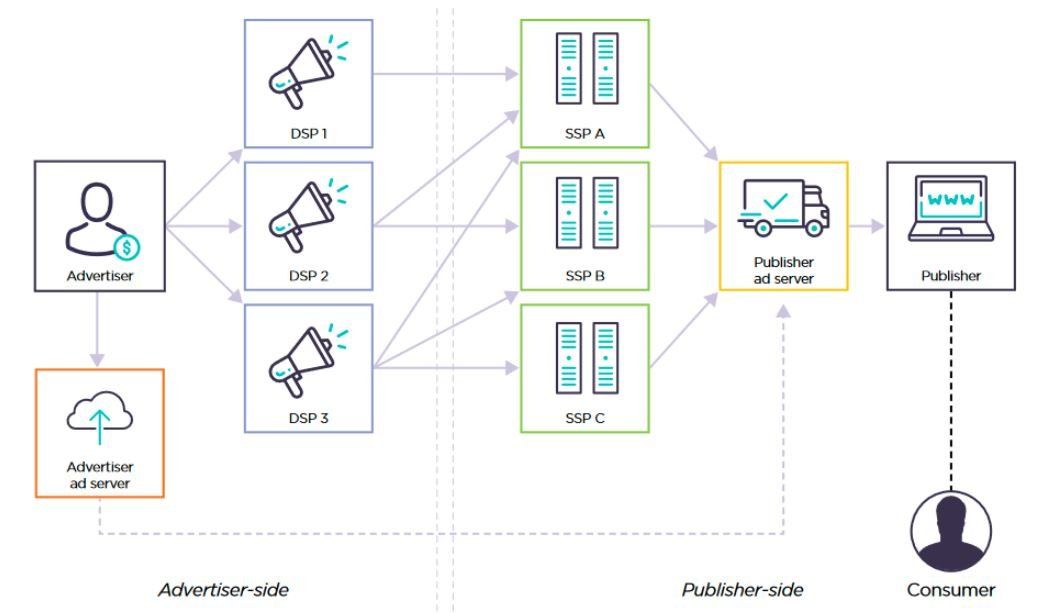

Both publishers and advertisers make use of ad tech services for the sale or purchase of ads. It is worth tokeep in mind that advertising space is subject to transactions that occur in real time and fully automatically, especially through auctioning processes which then lead to the delivery to the consumer. A consumer visiting a publisher’s site triggers a request for bids that goes through the supply-side platform(s) (SSP) a publisher uses. This bid can contain information on the consumer herself as well in order to get better targeted ads. The bid is then transferred from the supply-side platform to the demand-side platform (DSP) of advertisers where it is decided which bids will go back to the publishers’ SSP. If several DSPs have submitted bids, the SSP will conduct the auction and pass on the winning bid to the publisher which is then shown to the consumer.

c.f. ACCC’s Digital advertising services inquiry, p. 29, https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/Digital%20advertising%20services%20inquiry%20-%20final%20report.pdf

Google is the dominant player in ad tech

Along the steps of the described supply chain, the ACCC found that Google is omnipresent. Google’s browser Chrome continuously feeds consumers with ads while spending time on Google-owned platforms like Youtube. Moreover, Google operates SSPs and DSPs and several other ad tech services throughout the entire supply chain. The ACCC carefully considers efficiencies that could arise out of this vertical integration but eventually comes to the conclusion that there is potential for conflict of interests (c.f. p. 89f. of the final report). When Google conducts an auction in one of its SSPs but also participates as a bidder, there is an inherent incentive to prefer its own bid. Another example is that YouTube’s ad inventory is only offered to advertisers through platforms that are owned by Google, raising an incentive for Google to drive up prices for ad space.

The ACCC found Google to be dominant “as more than 90 percent of ad impressions traded via the ad tech supply chain passed through at least one Google service in 2020.” The vertical integration of Google in combination with its almost monopolistic market power raises serious concerns at the ACCC, with the chairman stating that adverse effects like “higher costs for both publishers” and a reduced quality in the online content shown are probable consequences of an inefficient ad tech market. This trend might have also been reinforced by the Covid-19 crisis as “the reliance on technological platforms...has entrenched [their] power”.

Self-preferencing of vertically-integrated digital firms is a problem that has been recognized in many jurisdictions, so the findings of the ACCC do not constitute an exception. Germany explicitly prohibited self-preferencing earlier this year with the introduction of § 19a (para. 2) of the Act against Restrictions of competition, a provision that is particularly focused on firms with a “paramount significance for competition across markets”. Shortly after, the Bundeskartellamt has launched investigations into Google, Facebook, Amazon and Apple, all under this new provision § 19a. This concern has also been considered already by the U.K.’s newly created Digital Markets Unit as self-preferencing is an “exclusionary tactic” that prevents new tech firms from successfully challenging the incumbents.

Consequences?

So what is the conclusion the ACCC drew from its findings? In the light of the competitive deficits that were found in the Australian ad tech market, the ACCC pointed out that the existing provisions of competition law are not sufficient to address the issues at hand. Rather the report established a need for new, sector-specific regulatory measures “for the benefit of business and consumers”. According to ACCC chairman Rod Sims this is in line with findings of other regulation agencies abroad with which the ACCC is “engaging very closely”.

Indeed, the U.K. has also conducted a study on the digital advertising market with the subsequent establishment of the aforementioned Digital Markets Unit. France’s competition watchdog L’Autorité de la Concurrence seems to be ahead of everybody, handing down a substantial fine of €220 million to Google in the summer of 2021 as a result of a settlement that Google requested (press release in French). The fine addressed Google granting preferential treatment to its own services in the ad tech sector, so it remains to be seen if (or rather when) other competition authorities follow suit and investigate Google’s behavior in that regard. Google naturally tries to escape new regulations, pointing out the positive effects of its ad tech services on the Australian employment market and economy. All those points were made in a press release the day before the ACCC’s final report was published (mind the timing…). The report might eventually lead to new regulation, just like in the case of the News Media Bargaining Code but it should be noted critically that the ACCC will not only maintain but reinforce its strong position in the Australian regulatory landscape. After all, the ACCC is making politics and could therefore create a situation of overregulation by advocating for new legislative actions.

Conclusion

As can be seen, Australia’s antitrust regime is mainly driven by the powerful ACCC which is in step with the times and certainly not afraid to take the GAMAs (former “GAFA” as Facebook rebranded to Meta) on. Due to the complexity of the supply chains in ad tech, it might take some more time until additional jurisdictions follow what the ACCC has already initiated in Australia: a call for stricter, more specialized rules in order to foster competition in the ad tech market.

Marco Schmidt holds an LL.M. in Law and Economics at the University of Utrecht, the Netherlands. He is particularly interested in matters of antitrust law and plans to pursue a career as a competition lawyer. Together with the Big Tech & Antitrust cycle, he investigates and researches current issues in digital antitrust. Being a German native, he is also fluent in English and Spanish and knows some basic French.

Read More

Watch Our Episodes