NEUROETHICS

Your Brain On Social Media

By Faissal Sharif

September 13, 2020

The digital generation: The iGen

In early 2020, nearly 59% of the world’s population had access to the internet with 49% actively using social media. That is 3.8 billion people scrolling, swiping, liking and commenting on platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Tik Tok - on average, 144 minutes a day.

While the benefits of social media are obvious - connecting to individuals globally, seek emotional support, access information, share ideas and raise awareness etc. - they come at a cost, especially for young people. While living with this environment of hyperconnection, statistics show that adolescents disengaged from social interactions in real life, whether it is with friends or with dates. Meanwhile, rates of psychological distress and depression rose dramatically over the last decade.

Jean Twenge, a professor of psychology at San Diego State University links this to the use of smartphones and social media. He calls this new digital generation born between 1995 and 2012, the iGen, and criticizes how social media increased teens’ fears of missing out (FOMO), loneliness and disrupted sleep. The empirical data on long-term effects is often contradictory and inconclusive. The ABCD (Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development) study, launched in 2015, follows nearly 12.000 children over the course of at least ten years, starting from when they are nine or ten years old. The study launched by the National Institute of Health promises new insights on the relationship between early smartphone use and brain development.

Addictive by Design

At the core of our tendency to spend hours in front of our smartphone screens are intricate mechanisms deployed by big tech companies to grow their arguably most valuable asset - our attention. As one of the most prominent figures spearheading the conversation, former Google employee Tristan Harris started the Time Well Spent movement. According to Harris, the digital revolution, powered by big tech in Silicon Valley, hijacked our minds as part of the Attention Economy. Social media platforms engage in a War for Attention - trying to get us hooked for as long as possible, engaging with content and ads. His Center for Humane Technology advocates for more socially meaningful interactions through social media by working with the public, policymakers and tech companies. Their work is featured in the upcoming Netflix movie The Social Dilemma by Jeff Orlowski, set to release on September 9th.

According to a report by Gallup, 52% of American smartphone users check their phones several times an hour or more. Among users between the ages of 18 and 29, one in five admitted to checking their phone every couple of minutes. Simultaneously, Google searches on Digital Detox and Digital Detox Retreats have risen steadily over the last ten years. Users are increasingly aware of the negative mental health consequences linked to social media and permanent digital connectivity. While initially turning a blind eye, tech companies have started to listen and are increasingly implementing Digital Wellbeing features in their products. Google’s strategy for AndroidOS involves, among others, app timers with daily limits and a grayscale mode to “reduce the attention-grabbing nature of many app icons”. As part of their Digital Wellbeing Experiments collection, one of their apps forces users on a “Desert Island” and limits their phone use to the most essential apps.

Silicon Valley native Jaron Lanier, “the father of VR” went one step further and wrote a book on

10 Reasons to Leave Social Networks. #1 on his list: You are losing your free will.

"When an algorithm is feeding experiences to a person, it turns out that the randomness that lubricates algorithmic adaptation can also feed human addiction. The algorithm is trying to capture the perfect parameters for manipulating a brain, while the brain, in order to seek out deeper meaning, is changing in response to the algorithm’s experiments; it’s a cat-and-mouse game based on pure math. Because the stimuli from the algorithm don’t mean anything, because they genuinely are random, the brain isn’t adapting to anything real, but to a fiction. That process -- of becoming hooked on an elusive mirage -- is addiction. " - Jaron Lanier

The neuroscience of Social Media: Dopamine, compulsion loops and slot machines

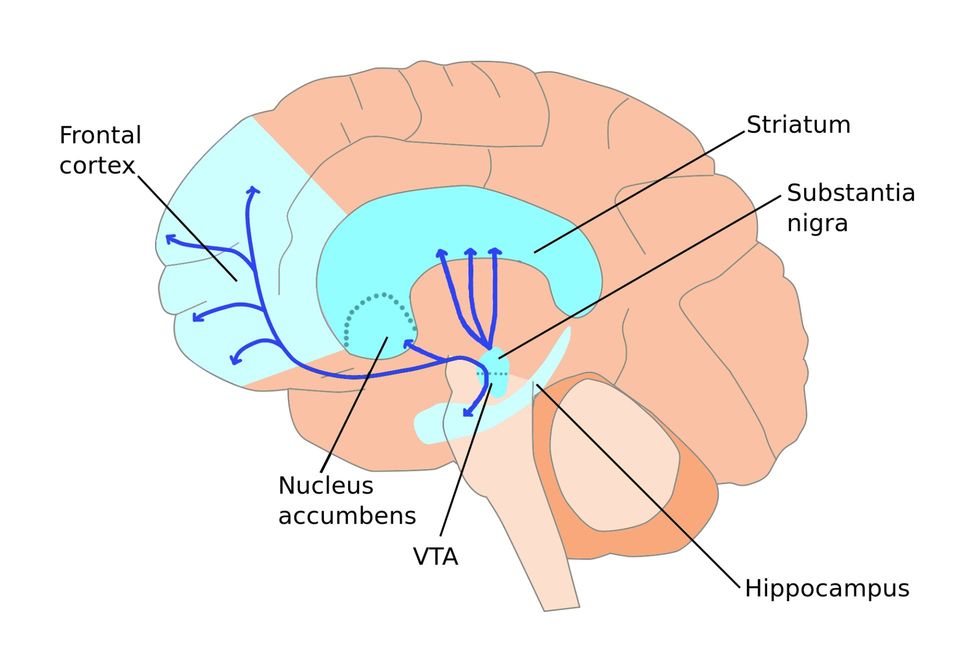

So how did we end up with digital detox retreats and apps sending you to a desert island? When Tristan Harris talks about tech companies taking part in a “race to the bottom of the brain stem”, he refers to one of the most fundamental, primitive features of the mammalian brain: the dopamine system. Neurons, the cells our brains are largely composed of, communicate through chemical messengers called neurotransmitters. These facilitate interaction between areas of the brain involved in different functions. The transport of dopamine, the main neurotransmitter responsible for pleasure and reward, follows distinct pathways in the brain depending on its function. Think of it as motor highways connecting brain regions for the efficient transport of information. The mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway is active in all sorts of human behaviour involving reward and reinforced behaviour, most commonly food, sex and

social interactions. So what happens when we get a new notification? A red icon flashes up, showing us new likes, comments or messages?

Image Source: Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology

We experience a small burst of dopamine in an area of the Midbrain called the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA). Through the neurotransmitter highways mentioned earlier, dopamine is passed on to the amygdala, which is responsible for strong emotional responses, such as fear and pleasure. Its connection to the hippocampus, where memories are produced, leads us to remember the cause of the dopamine surge - the reward itself, the like on Instagram. The VTA is also connected to the Nucleus Accumbens (NAcc) which is involved in motor function - the finger tapping, the swipe down to update. These associations between different brain areas and our memories reinforce dopamine-releasing behaviour. With each like, the response becomes more efficient, more hard-wired - we become hooked in a so-called compulsion loop.

This mechanism is crucial when thinking about survival - the pleasure of food or sex for reproduction - but can have adverse effects, as seen in addiction. Interestingly, apps designed to grab our attention act on similar parts of the brain as those involved in e.g. cocaine and amphetamine addiction, which rely on the dopamine system. Dopamine is not only released after a reward but also during reward anticipation, the period where we expect a reward to occur based on previous experience. Slot machines are designed to show spinning wheels for a couple of seconds to build up dopamine as a mere response to anticipation.

Instagram, for example, releases notifications in a batch, withholding them to increase expectation. Similarly, we reach out our phone as it vibrates, fuelled by dopamine because we expect a small reward in the form of a message or e-mail. App developers and user experience (UX) designers are well aware of these neurobiological underpinnings. Jaron Lanier speaks of a “social-validation feedback loop (..) exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology” - and he got a point. Long-term effects of social media on the brain, especially among the

iGen, remain elusive. However, with all that being said: You should definitely consider that digital detox.

Read More

Watch Our Episodes