DIGITAL DEMOCRACY

Why Facebook Users Matter in National Elections

By Francesco Vogelezang

August 30, 2020

Campaigning on Social Networks

Since the 2008 Obama Campaign, social media have become the routine in election campaigns. Most notably, this is because they provide a direct, immediate and unmitigated channel with voters that allow to circumvent the traditional role of professional gatekeepers (i.e. the press) typical of the 1.0 media era. They also enable politicians to extend their network outreach to larger lots of the electorate through the virality of their publications. This is ensured by algorithms that in the context of social media can be defined as “a system of criteria which are used to make decisions about the inclusion and exclusion of material and which aspects of said material to present in an algorithmically driven news feed”.

In the case of Facebook, the algorithm at stake is ‘EdgeRank’, that determines the content of the center column of a user’s homepage and represents a constantly updating list of stories from friends and pages. Although we know little about its current version, various scholars have shown that the popularity of an ‘Edge’ is determined by the extent of interactions it receives by users in the form of likes, reactions, comments, and shares. In this way, publications that are highly reacted can boost their overall visibility. This means that politicians can potentially expand their exposure to more voters as long as their followers recirculate these messages to their connections that do not follow the politician in question.

Yet, does this communication opportunity hold? What is its impact in national elections? And which users are the most active in augmenting the visibility of their preferred political actors? Do populist parties benefit more than their mainstream counterparts from this communication opportunity? In the next section, I show how I have tried to answer these questions.

Users’ Interactions: Predicting the Electoral Outcome

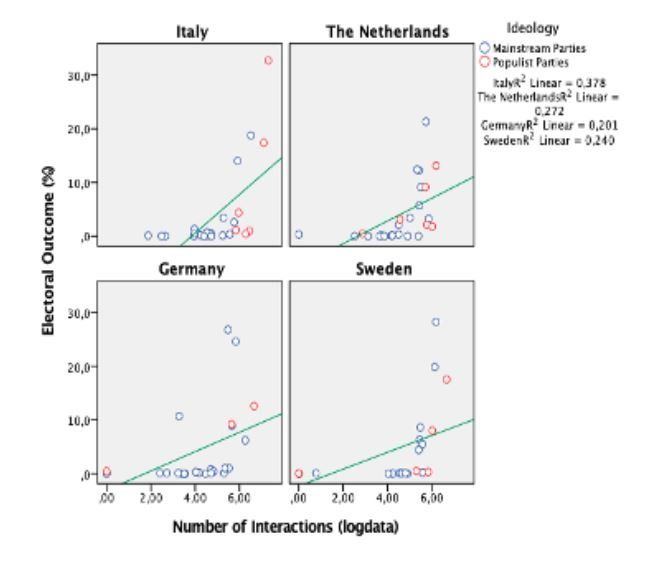

I have selected in total one hundred parties that ran for office across four European countries between 2017 and 2018: Italy, the Netherlands, Germany and Sweden. In total, I have identified twenty-one populist parties out of one hundred.I have then performed a multiple regression analysis to test the extent of interactions per publication that parties have posted eighteen months before the election day - my independent variable - against their final electoral result - the dependent variable.

In total, the model showed a positive moderate correlation of 0.48 while the R2 coefficient indicated that parties’ online presence alone could be predictive for 25.3% of their electoral outcome. Across the four countries, this impact varied. In Germany and the Netherlands, it had moderate positive relationships of 0.44 and 0.51. This means that the online presence of Dutch parties could be predictive of 27% of their electoral variance, whereas, for German parties, it could explain 20% of their electoral outcome.

Similarly, during the 2018 Swedish elections, parties also enjoyed a moderate positive relationship, as the coefficient amounted to 0.48. In this case, their presence on Facebook could predict 24% of their electoral variance. Finally, during the 2018 Italian elections, the online sphere even played a bigger role as parties had a strong positive relationship. This is confirmed by the correlation coefficient of 0.60, which indicates that it could be predictive for 37% of their electoral success.

Figure 1: Relation between Parties’ Online presence and their Electoral Result across Italy, the Netherlands, Germany and Sweden (Source: Own Research).

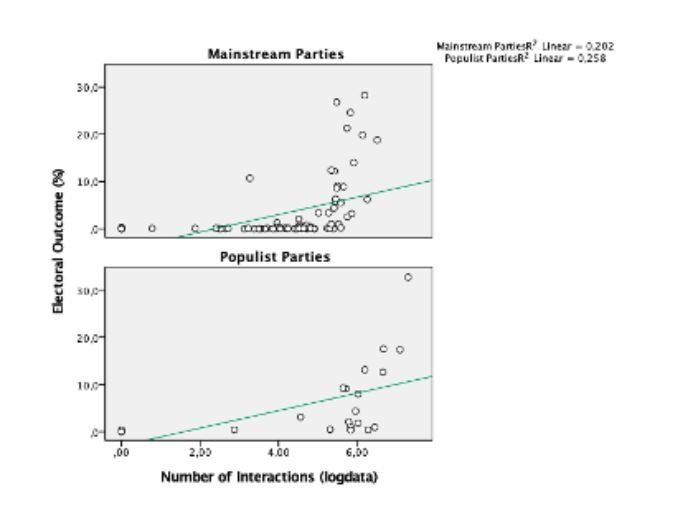

Concerning the difference between mainstream and populist parties across countries, both forces displayed moderate positive relationships, though populist parties had slightly higher coefficients. Mainstream parties have had a moderate positive coefficient of 0.44, which means that online dominance could be predictive on average for 20% of their electoral variance. On the contrary, populist parties had a slightly bigger coefficient of 0.50, thus indicating a moderate positive relationship. Hence, their Facebook dominance could be indicative for 25% of their electoral success.

Figure 2: Relation between Online presence and Electoral Result between Populist and Mainstream parties (Source: Own Research).

Implications for the 2020 US Elections

What will be the impact of users in recirculating online information on Facebook during the next US elections? That we cannot know… What we can do, however, is to draw some conclusions from past experience and put into context for 2020. During the 2016 US elections, Alcott and Gentzkow found that approximately a quarter of voters have shared a fake news story at least once. Concretely, they have demonstrated that if a fake news is shared 38 million times, it can potentially generate more than 760 million clicks. Moreover, social media bots were found to play a central role as about a fifth of Clinton’s and Trump’s tweets have been automatically generated. Yet, pro-Trump bots produced about four times as many tweets as pro-Clinton bots.

Though we are not sure about the impact of parties’ online presence in the US electoral context, fake news’ generation through automated bots seems the perfect cocktail to expose a larger portion of users to specific political content. As these elections will probably be one of the most politically tense in history, there is the precondition to observe the fervent circulation of extreme political information, whose virality will be determined by ‘EdgeRank’. Concretely, this means that users will actually regulate the circulation of political information on Facebook. Yet, they will perform this ultimate role from their isolated and tailor made echo-chamber.

Read More

Watch Our Episodes