ENVIRONMENTAL SENSITIVITY

Sensitive Souls Connected

Why are some individuals more sensitive to their environment? And what is the neurobiology behind it? This blog article sheds light into the neurobiological trait sensory processing sensitivity, the historical development of the concept and the interplay between genes and environments.

By Nico Amiri

March 7, 2021

Numbers

Roughly three out of ten individuals are highly sensitive. That means that more than a quarter of society has a special trait and, that is, sensory processing sensitivity (SPS) - or high sensitivity. What does it mean exactly to be a highly sensitive person (HSP)? The trait refers to the intensity of processing internal and external stimuli, which is relatively higher in comparison to the non-highly sensitive portion of the general population, and higher empathy as well as increased emotional reactivity (Greven et al., 2019).

Neurobiology

Both terminologies and the biopsychological concept were coined and developed by psychologist Elaine Aron and her husband Arthur Aron in 1996 and the years thereafter. In the early years of research, the trait was qualitatively measured by the Highly Sensitive Person Scale (HSPS) questionnaire (Booth et al., 2015). Over the course of the last 20 years, the primary psychology-oriented research has been extended and enriched by gene and genome studies as well as brain imaging studies. The concept has been given a biomedical fundament.

There is a variety of genes, thought to play a crucial role in the neurobiological development of SPS. Among them there is the serotonin transporter, encoding for the corresponding gene 5’-HTTLPR gene. This gene is present in two variants: a short (S) and a long (L) variant. Each individual carries one gene (variant) from the mother and on from the father, thus there can either be S/S or S/L or L/L combinations in the offspring. Carriers of the two short variants are more likely to develop SPS and subsequently to be highly sensitive (Caspers et al., 2009).

Genes and gene variants are one side of the coin, the other is the environment. There is epigenetics, for instance, referring to the package of DNA, for instance; it regulates if certain genes are actually translated into proteins and subsequent traits. Through so-called gene-environment interactions, the environment influences how the genetic ‘toolbox’ is used. In the case of SPS, the circumstances an individual lives in are crucial to determine how they are affected by their trait. This is called the differential-susceptibility hypothesis

(Ellis et al., 2011).

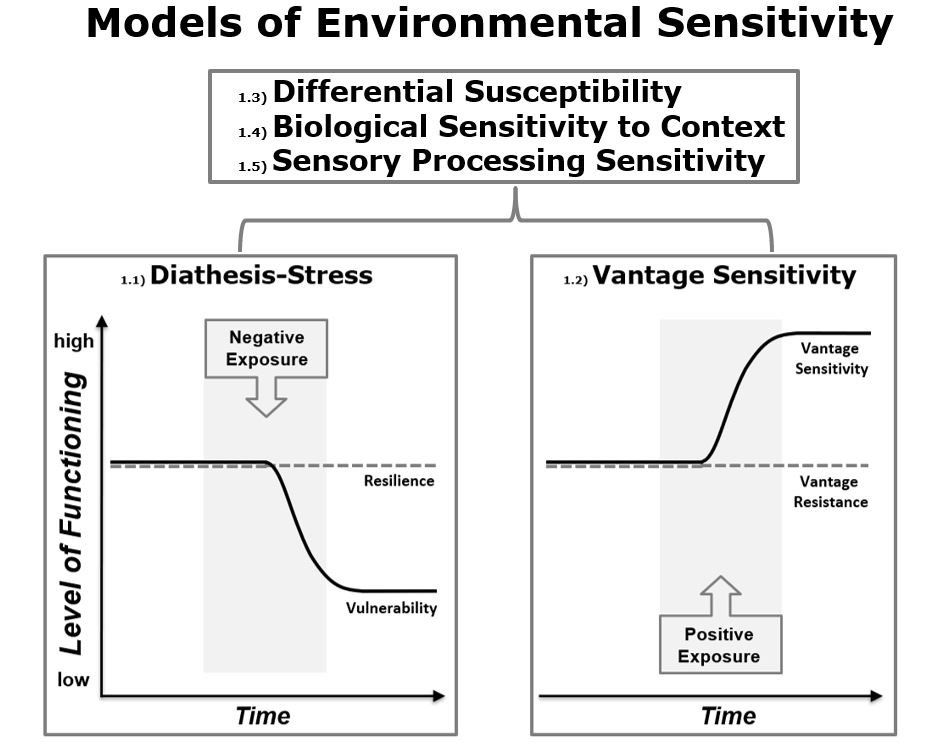

Figure 1. Illustration of the different models describing individual differences in Environmental Sensitivity: Diathesis-Stress (1.1) describes variability in response to adverse exposures, and Vantage Sensitivity (1.2) variability in response to supportive exposures, whereas the remaining three models Differential Susceptibility (1.3), Biological Sensitivity to Context (1.4), and Sensory Processing Sensitivity (1.5) describe individual differences in response to both negative and positive experiences. Consequently, Models 1.3, 1.4, and 1.5 reflect the combination of Models 1.1 and 1.2. Adapted from Figure 1 in “Individual Differences in Environmental Sensitivity” (Pluess, 2015), Author: Mpluess, CC BY-SA 4.0,

As shown in Figure 1, the type of environmental exposure is crucial for the level of individual functioning. Negative exposures as, for instance, an adverse childhood, are reported to affect the highly sensitive person negatively (Aron et al., 2005). A positive environment, however, can mean benefits for the HSP, as “developmental enhancements” (Ellis et al., 2011).

To grasp the essence of this biopsychological model, we can, for the sake of simplicity assume that there is a dichotomy, meaning there are only two categories: highly-sensitive individuals and individuals without SPS. However, it has to be mentioned that there might be actually more than two categories. It could be the case that SPS is a ‘spectral’ trait: humans might be neither highly sensitive and empathetic or cold-hearted and non-empaths; it could rather be the case that the intricate play between (epi)genetics and the environment determines where on the spectrum an individual is located at a given time point in life.

Nico Amiri, 24, holds a bachelor’s degree of Biomedical Sciences from Maastricht University with a semester at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, following a minor in neurosciences. As of September 2020, he is following a Research Master in Biomedical Sciences, specialising in Genetics & Genomics. His research interests are neurogenomics, sensory processing sensitivity, and Alzheimer’s Disease. He is a member of the Neuroethics cycle at the Institute for Internet & the Just Society.

Read More

Watch Our Episodes