EU REGULATION

Illegal vs Harmful Online Content

By Francesco Vogelezang

December 2, 2020

Leo Moraes

Online content regulation has recently gained political momentum in the European Union (EU), most notably after the 2016 United States’ (US) elections where fake news’ propagation and hate speech dominated the salient phases of the campaign. This was evident as Alcott and Gentzkow found that while 62% of US adults accessed news on social media, the most popular fake news stories were more shared than the mainstream ones. Put into numbers, they discovered that if fake news is shared 38 million times, it can potentially generate more than 760 million clicks. This is alarming considering that a study conducted by the Pew Research Centre in 2018 discovered that 67% of US adults used social media to access political news.

In light of these threats, European regulators have tried to tackle the issue at the national level. This was mostly evident in Germany and France where hate speech laws were soon adopted but criticized by many. This is because of two main reasons. First, these bills significantly restrict information availability because online platforms, due to the threat of punishment, have an incentive to take down content preemptively. Second, such obligations are deemed to be disproportionate as platforms have to act in unreasonable short amounts of time. As occurred in France, the hate speech law was ruled unconstitutional on these grounds.

However, this is not it. The EU is set to pass an ambitious framework that aims to regulate the market conduct of large online platforms acting as gatekeepers. This is the Digital Services Act package that would modernize the intermediary liability regime established by the 2000 eCommerce Directive by introducing the concept of intermediary responsibility. It would act on two main pillars. First, it would clarify the responsibilities of digital services in light of users’ fundamental rights. Second, it would create ex-ante competition rules to regulate the conduct of online platforms while securing innovation and transparency in the market. If adopted, content regulation could be legally enshrined at the supranational level as online platforms would be subject to more stringent rules across the EU27.

Nevertheless, despite the ambitious character of the proposal, the EU should not rush into “easy-to-adopt-solutions”. For the DSA to be effective, it is pivotal to safeguard the country of origin principle, one of the success stories of the single market, while keeping online platforms accountable to regulators. Therefore, in the paragraphs that follow, I touch on some of the main tensions that should be addressed by EU regulators. Precisely, I argue on the fundamental difference between harmful and illegal content and how such a distinction should be governed by the right political architecture.

The first area of tension is represented by the realization that content matters and that is not a fixed concept. This constitutes one of the main points that emerged after the two consultation rounds organized by the European Commission. On the one hand, we can observe how online platforms do not want heavier obligations in regards to content regulation. Thus, they underline their intermediary function, as stipulated by the current Safe Harbor regime. This was strongly emphasized by the Facebook White Paper on Online Content Regulation, but rejected by the European Commission. As Gillespie points out, this can be largely explained by the irreconcilable contradiction that platforms face: they pretend to make systemic choices about what users see and say while being classified as mere conduits. On the other hand, diffuse interest groups are also against but for different reasons. Hence, they believe that information society providers should not perform such an unrestrained policing role in determining what is lawful or not on their platforms. As they argue, this would unjustly undermine users’ freedom of speech and right to information in the online sphere.

This opposition mainly arises because of the inherent struggle between users’ rights and the nature of information society at large. This is clearly evident when balancing freedom of speech with platform’s intermediary exemptions as actions to protect users’ rights in the online sphere seem to collide with self-regulatory initiatives. For instance, this is the case with natural language processing (NLP) algorithms that cannot grant, at the moment, sufficient certainty in distinguishing between illegal and legal content. Spoerri indeed underlines the high false-positives rates as filters cannot properly take into account factors such as context or satire. It follows that if companies were to adopt such ex ante requirements, they would simply reduce their range of tolerance, hence prioritizing over-blocking to avoid eventual legal risks and enforcement costs. This could have serious repercussions on users’ rights, as opposed to the initial aim of the measure that is to protect them. As occurred with the Facebook Oversight Board, such a leeway could result in a de facto creation of an online constitutional order. This would indeed undermine the capacity of offline regulators to influence the conduct of online actors. Therefore, it is necessary to ensure that platforms do not enjoy such discretion in balancing users’ rights in the online sphere and that they are accountable to regulators.

One way to solve this issue could be the establishment of a specific legal regime that differentiates between illegal and harmful content with the aim to specify companies’ responsibilities. A recent study commissioned by the European Parliament offers a good starting point to build an appropriate framework. Accordingly, illegal content would encompass a large variety of information items that are not compliant with EU and national legislation, such as hate speech, incitement to violence, child abuse material and revenge porn. Instead, harmful content, refers to information that does not strictly fall under legal prohibitions but that might nevertheless have harmful effects. Inter alia, these include cyberbullying and mis-or disinformation.

How could this work in practice? In the case of illegal content, online platforms should be entitled to ex ante removal, but if and only if available NLP algorithms are sufficiently precise in detecting such a threat. For instance, this is the case for child pornography, where available evidence indicates that such system works effectively. On the contrary, for terrorism and hate speech, this does not seem to be efficient as interpretation heavily depends on mediating contextual factors that are oftentimes overlooked by existing filtering systems. It is therefore crucial for the EU to adopt a sectoral approach with the aim to determine in which areas NLP is sufficiently reliable in identifying illegal content. This is not currently the case in the eCommerce Directive that broadly encourages:

“the development and operation of technical systems of protection and identification and of technical surveillance instruments made possible by digital technology” (recital 40).

To tackle these technical and legal shortcomings, suspicious borderline content should be labelled by platforms and reported to a responsible monitoring body. This would allow the delineation of horizontal legal criteria based on previous case-to-case assessments by regulators. Most importantly, it would instruct platforms on how to identify content when suspicion arises, hence moving the monopoly of interpretation from the private to the public. For this process to be effective, nevertheless, it is fundamental to uphold the transparency principle as to oblige online platforms to disclose the criteria behind preemptive filtering. This regulatory prerogative seems to be included in the DSA package in order to keep platforms accountable and eventually punish them for non-compliance.

In addition, users could prove to be useful here. Thus, encompassing and transparent notice and take-down mechanisms should be put in place as to allow citizens to flag the allegedly infringing material. Online platforms would then have the choice to remove it based on pre-determined criteria defined by regulators or, again, report it swiftly to the responsible watchdog authority. Throughout this process, remedies should be available to complainants as to appeal decisions to, or not to, revoke content. Likewise, adequate penalties for abusive notices should be available to regulators. When it is ascertained that the flagged content is illegal, platforms should be given adequate and reasonable time to remove it, provided that it will remain labelled throughout the whole process.

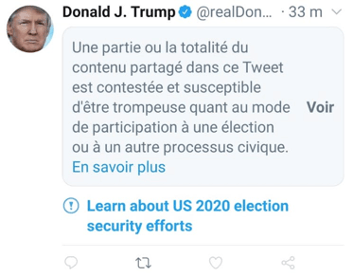

In the case of harmful but legal content, the situation becomes more complicated as it consists of information that may be inadequate for certain categories of users, but whose legality varies significantly across Member States. This poses an extra layer of difficulty to the country of origin principle as the institutional context at stake plays a crucial role in determining online harm. To solve this, labelling could once again be instrumental because it would allow to signal the dangerousness associated with certain information. In this case, regulators could potentially delineate a narrowly-defined duty of care for digital platforms with the aim to ensure people’s safety and wellbeing in the online sphere. This could be associated to obligations to label contestable and susceptible content, as occurred with Twitter during the 2020 US elections.

Nevertheless, such an action should not stop at the detection stages. Instead, it should provide for long-term legal harmonization. To this end, as proposed by the DSA package, this regulatory architecture could be governed by an independent EU body tasked with monitoring platforms’ conduct inside the internal market. This is important because platforms have different community guidelines as they prioritize certain categories of content and actions based on their technical and political architectures. Moreover, the establishment of a supranational body would allow to streamline legal differences across Member States in the identification of harmful content by allowing the creation of a supranational definition. Hence, national divergences constitute one of the most criticized aspects of the eCommerce Directive as the current legal regime is characterized by persistent cross-border uncertainty.

Under this scheme, online platforms would still retain the prerogative to identify harmful content based on users’ complaints and automated filtering in safe areas. However, the decision to eventually strike down doubtful information would be dependent on predefined criteria by regulators. As such, labelling could prove useful again as it could help in solving another legal tension: the Good Samaritan Paradox. The latter refers to the situation where information society providers would lose their intermediary exemption in the moment they decide to take significant action to protect users’ rights. To solve this, a conditionality-based Good Samaritan Clause could be introduced to guarantee intermediary protection. As previously discussed, platforms should be encouraged to label harmful content and disclose the rationale behind such filtering with the promise of being exempted from direct liability.

Similarly, such a conditionality-based approach could be offered in conjunction with content variegation requirements. This could be extremely helpful in regulating harmful content as this category includes fake news and mis-or disinformation. The latter is a very sensitive area that has so far been approached through voluntary self-regulation, as in the case of the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation. However, this approach has been questioned throughout the covid19 pandemic as platforms have significantly failed to contain the spread of misleading information. In election times, this is critical as social media could potentially dictate the flow of the political conversation, thus alimenting online echo-chambers and filter bubbles. Likewise, if governments were to adopt rigid solutions, they could be accused of censorship. To solve this stalemate, the exposure to ideologically diverse content could serve as good compromise. Moreover, as Sloss proposes, online platforms could be entitled to identify persistent offenders in spreading misinformation, which would then be removed after receiving a significant amount of warnings. For instance, this approach could be pivotal in reducing the power of social media automated bots.

Overall, the distinction between harmful and illegal content could be beneficial in balancing users’ rights in the online sphere while keeping online platforms accountable to regulators. However, it is evident that such an approach should not just rely on rigid obligations but on flexibility. As shown by the French hate speech law, excessive impositions on platforms could provoke undesired consequences that might undermine users’ rights in the online sphere. This is because, on the one hand, information service providers could enjoy excessive discretion in taking voluntary actions to regulate content’s circulation. This would strengthen their position in the market, thus de facto making them rights’ gatekeepers. On the other hand, with a self-regulatory approach, they would have an incentive to over-remove content that is not illegal.

Nevertheless, this tension could be addressed by differentiating between harmful and illegal content, as a sustainable and fair compromise could be struck. As I have described, regulators have a variety of options in their hands. However, the situation could easily become suboptimal if they decide for easy and rushed solutions. The slope is slippery but the DSA nevertheless provides a wide array of possible regulatory instruments. Thus, European regulators have the upper hand to take significant steps in regulating platforms’ conduct across the Union and protect users’ rights. A distinction between harmful and illegal content could indeed serve as a good starting point.

*This post was written as part of the Regulation and Digital Economy class taught by Bertrand Pailhès, Benoît Loutrel & Doaa Abu Elyounes at Sciences Po Paris.

Read More

Watch Our Episodes