DIGITAL ECONOMY

Digital Taxes: A Fake Solution For A Real Problem

Real solutions to the tax avoidance and advantageous taxation digital supergroups enjoy can only be international and structural, updating practices of international taxation that have now become obsolete. They cannot be a mere quick fix. Voters demand it, the sustainability of our economic models requires it.

By Nicola Bressan

January 26, 2021

“We’ve got to be talking about taxes. That’s it: taxes, taxes, taxes. All the rest is bullshit in my opinion.”

It is with these words that the Dutch historian Rutger Bregman, at the worldwide reunion of private jet users and caviar aficionados that is Davos’ World Economic Summit, addressed one of the most pressing challenges today’s policymakers have to face: tax avoidance. Eroding the depth of public resources, damaging the public’s faith in democracy and the system and causing tension between countries, the phenomenon has recently grown into one of crucial political and policy importance. But what does tax avoidance exactly mean?

Using the OECD’s definition:

‘A term that is difficult to define but which is generally used to describe the arrangement of a taxpayer's affairs that is intended to reduce his tax liability and that although the arrangement could be strictly legal it is usually in contradiction with the intent of the law it purports to follow.’.

As this phrasing points to from the get-go, tax avoidance is indeed a concept whose boundaries are quite blurry, both for experts and - even more so - for the general public. Oft-mistaken with the more immediately comprehendible tax evasion, the confusion surrounding what tax avoidance practically consists of is omnipresent in public debate. Like most things relating to policy, nuance is key: in the spectrum between a perfectly acceptable tax optimisation practice (such as, for example, the use of tax credits for research and development or green energy) and tax evasion (deliberate misreporting of revenue), tax avoidance measures place themselves in the grey middle area.

An ever-growing problem

For all practical intents and purposes, the term tax avoidance refers to the multitude of mechanisms put in place by multinational groups so as to move their profits from high-tax jurisdictions to jurisdictions with a lower imposition rate. From sophisticated accounting schemes with creative names – the infamous “Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich” and the “Single Malt” definitely stand out – to simpler loopholes allowing for artificially inflated transactions between subsidiaries of the same group, the various tools employed are complex and detailing them would go far beyond the scope of this article. What is interesting to note is how these practices have evolved over the years both in terms of scope and public attention, from an exotic matter familiar only to the most daring of tax planners, to an issue that is front, right and centre in the policy agenda.

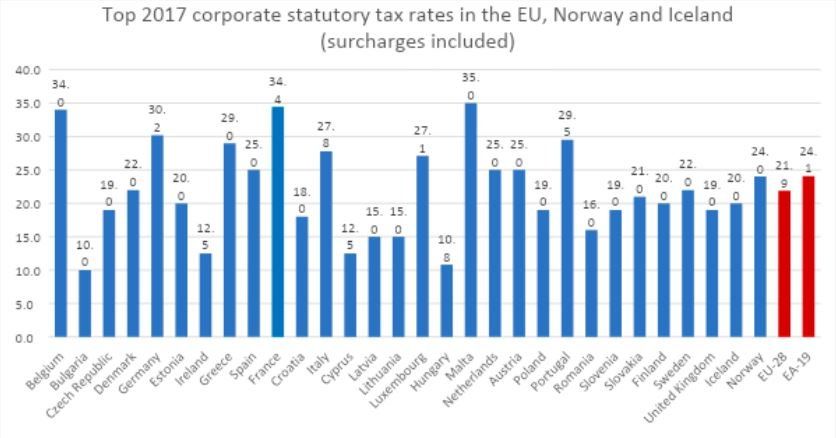

Taking a relatively cohesive bloc of countries such as the EU, it is easy to see how corporate tax rates can differ wildly, making the incentive for tax avoidance more than tangible. Source: European Commission.

While by no means new – the first OECD report on the matter goes as far back as 1978 – worldwide corporate tax avoidance has grown into a 500 to 600 billion USD yearly hole in public budgets (Crivelli, de Mooij, and Keen 2015; Cobham and Janský 2018), 1% to 1.3% of global GDP. Taking country-specific estimates, the evolution is staggering: the loss in revenue for the French government, for example, went from less than 1 billion EUR in year 2000, to 13 billion in 2008, and past the cap of 30 billion starting from 2013 (Vicard, 2019). This exponential growth can be easily explained by taking into account two phenomena of our generation: the acceleration of economic interdependence and the digitalisation of our economies.

Structural legal challenges

If the former is self-explanatory, the latter isn’t. Among the multi-faceted challenges digitisation brings to our production models, democracies and daily lives, there is that of taxation. The definition of what fair taxation is, as well as its enforcement, are matters that our connected and internet-reliant world makes all the harder to answer. Traditional frameworks to determine taxable entities and their imposable amounts – which stem all the way back to the early 20th century – are in fact hardly applicable to the modern production of added value and profits.

One of the most basic of concepts in our tax jurisdictions, the idea of a ‘permanent establishment’, is for instance largely inapplicable to the digital economy: if generally, taxing rights are computed from the profit collected from a fixed presence within a given territory, the business model of most tech and digitally-oriented conglomerates can generate great amounts of revenue with little to no actual physical presence in a country. Defining a ‘nexus’, a taxable presence within a country, therefore becomes far more complicated.

Secondly, the intangible nature of the goods and services sold makes it so that defining value creation, and even more importantly linking value creation to tax regimes, is challenging. As Olbert and Spengel (2017) put it, taking the usage of user data as a marketable good as an example, if ‘the concept of data as a contributor to value creation is established, the question of how to attribute value to the generation, storage and use of data is still unanswered’. In a more down-to-earth way: if a Brazilian user, by willingly sharing his data, creates value for an American platform, shouldn’t that be taken into account in the calculation of owed tax? In this sense therefore, the usual principle of arms-length transactions and the current transfer-pricing models used to allocate taxable profits within value chains fall short of effectively capturing and appropriately taxing the new, digitalised ways to produce added value.

As these examples show, the phenomenon of tax avoidance is vastly exacerbated by the digital economy. While crucial, they are by no means the only causes contributing to making digitisation a factor of aggravation: abuses of VAT exemptions, the hardship in ‘characterisation of income’ (many e-commerce transactions may, for instance, be classified as royalties), the heavy reliance on R&D cost subsidies and the advantageous criteria for depreciation specific to digital business models also figure on the list. This discrepancy is one companies in the sector do not fail to capitalise on: if on average, SMEs in Europe are taxed at an implicit corporate tax rate of 23%, the largest companies of the digital sector only pay an effective corporate tax rate of 9% (PwC and ZEW, 2018). Beyond the ethical concerns and the missing governmental revenue tax avoidance brings forth, the disloyal competition is an aspect that should not be overlooked.

The relative failure of international policy initiatives

The growing awareness of this injustice has, slowly but surely, translated itself into a growing policy interest to the matter. Firstly, from an international point of view. The most relevant international initiative tackling the issue is, undoubtedly, the OECD’s ‘Addressing Base Erosion and Profit Shifting’ (BEPS) 2013 document and its ensuing Action Plan, finalised in 2015. With the cooperation of 135 countries on the project (albeit to a varying degree of involvement), and around 85 countries -representing more than 90% of world GDP - having signed the Multilateral Instrument on BEPS, the project is widely seen as a successful soft law endeavour, instrumental in setting a concrete worldwide benchmark, and bringing the topic to the forefront of international cooperation. Its biggest achievement is, arguably, having established universally recognised definitions of Controlled Foreign Company rules, Permanent Establishment status and alignment of transfer pricing criteria to value creation.

Yet, the process being largely consensus based and having the explicit aim of being flexible and practical enough to be implemented rapidly in vastly different jurisdictions and tax regimes, one cannot imagine it to be a holistic, all-solving framework. In fact, this first truly global initiative on the matter is to be seen as the groundwork upon which to build further so as to tackle and bring down tax avoidance, rather than ‘the final destination of international tax law reform’ (Reuner and Xu, 2019).

More directly relevant and impactful to the topic of digital taxation are the recent initiatives contained in what has generally been dubbed ‘BEPS 2.0’. Consisting of two pillars, they aim to solve at the root the specific challenges of the digitalization of the economy that we have addressed earlier: on the one hand, the solving of the territorial and nexus-related issues that plague digital services taxation rights, and on the other the establishment of a minimum global corporate tax rate as well as of a tax on base-eroding payments.

Both of these areas of development have the potential to significantly disrupt long-standing paradigms in taxation processes, as well as de facto impacting on the level of sovereignty jurisdictions have in setting their effective corporate tax rates. Depending on where the minimum tax is set, for instance, some low-tax jurisdictions such as Hungary or Ireland might see companies legally resident within their territory being taxed above the threshold set by their own legislators. This would be due to the parent company being directly taxed in its territory of residence in case its foreign subsidiaries’ profits were deemed to have been taxed below the OECD-set minimum rate.

Similarly, the technical difficulty and high sensitivity of the stakes linked to choosing the proper means of allocating taxable profits on the basis of where digital services are consumed rather than where permanent establishments are located characterise the setting of new, digital economy-tailored, profit allocation rules. It is for these reasons that the negotiations on the guidelines to be adopted globally have been fraught with political contrasts and vested interests, which have slowed down the negotiations to a screeching halt: initially meant to be completed ‘before the end of 2020’ (G20, 2019), the initiative is still far from having reached a final stage, with the US Treasury secretary Steven Mnuchin having announced on June 17, 2020 that the talks had ‘reached an impasse’ . While most officials maintain officially that the global option through the OECD is the preferred one, more and more jurisdictions – as we will see – are turning towards unilateral solutions.

The proliferation of digital services taxes

These interim solutions have been mostly centred around one typology: digital services taxes (DSTs). Computed on revenues instead of profits, these measures circumvent one of the most crucial of issues plaguing tax avoidance: as revenues are generally harder to underreport without falling into the scope of blatant tax evasion, levies based on pre-VAT gross turnover would manage to capture a higher share of the actual value created in a given jurisdiction. This is, though, only partly applicable to the digital economy. Beyond this issue, the complexities and shortcomings of such solutions are significant.

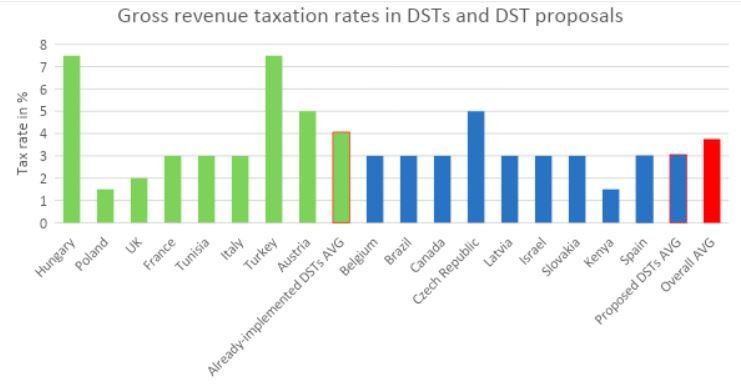

16 countries have either already implemented or announced to be planning to adopt such revenue-based taxes.

The policy convergence in the field, while not absolute, has been noticeable: it is in fact France’s 2019 ‘Taxe GAFA’ (GAFA being an acronym for Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple, which should already provide us with a hint of the aimed targets of the initiative) that has spearheaded the worldwide wave of adoption of digital services taxes. While not being the first country to have enacted a specific taxation measure addressing the imbalances in imposition of large digital groups - for example, Italy had adopted (but never implemented) a digital transaction tax in 2017, and India has been imposing an equalization levy on non-resident service providers ever since 2016 – France and its tax have had an incontestable role in establishing a model and a benchmark for what today would be called a fully-fledged DSTs. Firstly, in pushing jurisdictions into accepting DSTs as the tool of choice to tackle these disparities, and secondly in imposing many of its mechanisms as the common pre-OECD consensus policy reference on the matter.

While not entirely convergent, we can see that the majority of jurisdictions having implemented or having declared to be planning to implement a DST have opted for a rate hovering around 3%. The similarities do not stop there: they also concern the applicable thresholds and, to a lesser extent, the absence of sunset clauses and the definition of imposable services.

An analysis of the divisive measure, which ever since its adoption by the French Parliament has become the spark of a transatlantic trade dispute, is necessary so as to understand its concrete implications, especially as it is fully possible to take the French example as a relevant case study for the rationale and justifying reasoning behind Digital Services Taxes. Firstly, when it comes to the types of services it is aimed to: digital ‘interfaces’ allowing users to enter in contact with each other with the goal of selling goods and services and targeted advertisement services mobilizing user data.

This delimitation of the taxable services falling under the imposable base of the tax is more than relevant, as it excludes first-hand some digital companies (or big multinational companies who source a significant yet not majoritarian part of their income digitally) whose business models do not revolve around these two services: among these, for example, cloud computing, direct provision of intangible content, non-targeted advertisements.

Companies like Spotify or Netflix, for example, whose business models do not have an intermediation element, and rely mainly on subscriptions for revenue, are not liable to pay the tax. Furthermore, it cuts out some parts of the business ventures of the very companies targeted by the tax itself: in fact Apple and Amazon have a large subset of their revenues which do not fall under the criteria above, either because they are offline sources of income (Apple’s hardware sales being an example) or because they are neither based on targeted publicity nor on intermediation (Amazon’s cloud computing services, for instance).

Secondly, so as to establish which companies fall within the scope of the DST, the criteria are twofold and both based on the yearly revenue of the services mentioned above: the company has to exceed 750 million EUR of worldwide targeted services’ revenue, and 25 million EUR of targeted services’ revenue in France. The obvious goal being here to limit the tax to multinationals of significant size, partly because they are those responsible for the highest share of tax avoidance eroding French taxes, partly so as to compensate for the network effects and returns to scale they enjoy over their smaller competitors in a market that is characteristically oligopolistic.

Potentially distortionary, it may be argued that this limitation to companies above an arbitrary threshold leads to differentiated treatment, directly contrary to the principle of tax neutrality. A similar criticism encountered is the one decrying the arbitrary nature of the threshold chosen, which many have interpreted as being deliberately set so high – rather than according to a legal or economic rationale - so as to carve out European and French companies from the imposable criteria, but being formally compliant with non-discrimination principles in WTO, OECD and EU rules. According to governmental and third-party estimates, the number of imposable companies would range from 30 to 40, out of which the only wholly French-owned company would be Criteo. What appears clear is that the face burden of this tax levied would be borne mostly by US-based companies, who in the latter of these estimates comprise as much as 17 companies of the 26 listed.

The ineffectiveness of digital services taxes: the Google Case study

Finally, the means of calculation of the tax itself: even when deliberately disregarding the widely documented distortionary effects of revenue-based taxation, the limited effectiveness of these measures are evident. The chosen rate of 3% on the revenues -while higher than most other gross receipt taxes (in the USA for instance, 7 states have gross receipts taxes on the totality of transactions, with statutory rates going from 0.02% in Tennessee to a maximum 1.95% in Delaware) to make up for a smaller tax base - mentioned by the services above is by no means enough to compensate for the discrepancy tax avoidance brings to the table. Even only a superficial look at the revenue created by the tax – in the fiscal year 2019, the French government has only collected 350 million EUR from the tax– would make such a statement clear. Yet, providing a concrete example here would help in better visualising the minimal effect of the tax on the profitability of the firms.

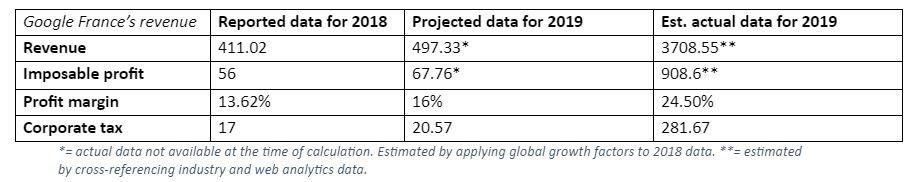

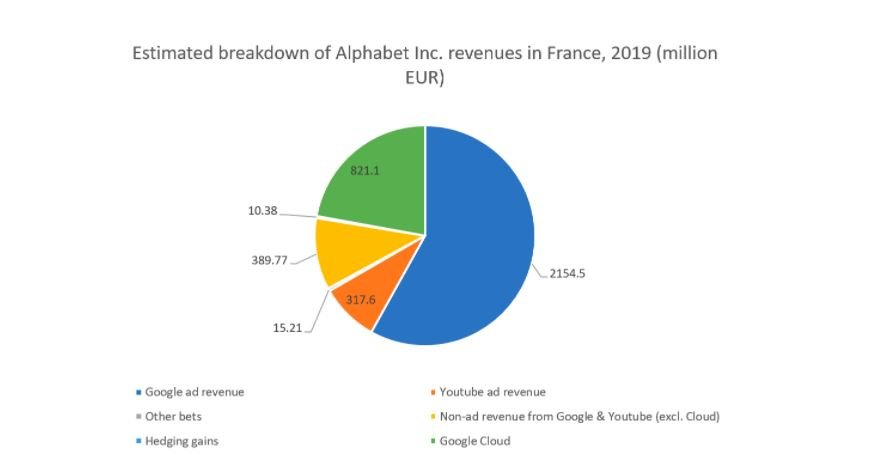

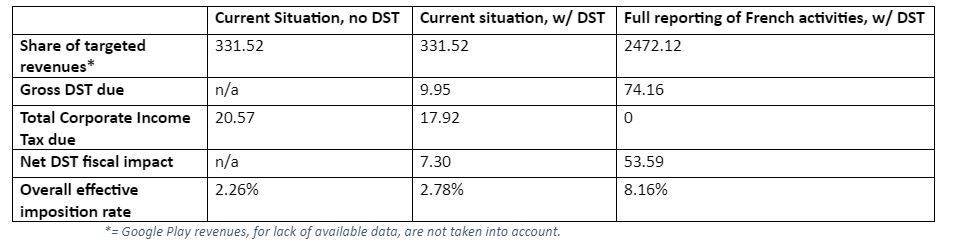

As we can see from the estimate above, basing oneself off of market shares, realistic growth factors and the worldwide revenues reported by Alphabet Inc. for the fiscal year of 2019, it is possible to estimate Google France’s 2019 revenue to be around when 3708.5 million EUR, 7 times higher than the amount that we can reliably presume Google to have actually reported to the French authorities. Its breakdown would be the following, with only around 68.7% of its activities (Youtube and Google’s ad revenue) falling under the scope of the digital services tax.

Note: the calculations for ‘Hedging gains’, ‘Other bets’ and ‘Non-ad revenue from Google & Youtube (excl. Cloud) are estimated by holding constant the global proportion of revenues. Source : calculations from 2019 yearly report, 2018 declared revenues in France, web analytics, industry reports and benchmarks.

More importantly still, the actual impact of the DST would really only marginally help in making Google’s actual imposition rate fairer and closer to France’s 31% corporate tax rate. Computing the amount of corporate tax actually paid to the theoretical imposable profits, the result is of an estimated effective imposition rate of 2.26%. As the total amount of ad revenues Alphabet receives is of 2472.1 million EUR, the potentially due DST amount is of 74.16 million EUR, by no means enough to compensate the gap with the corporate tax that, basing ourselves off of our prior estimate, ought to be paid in France in the first place : the effective imposition rate, considering that the DST is deductible from corporate income tax, would in fact be of 8.16%. Ironically, Google France would be artificially in deficit for the year, the amount of due DST tax being higher that the net revenues declared so far.

Furthermore, this extreme scenario would apply only in the case where the totality of revenues stemming from French users were to be declared by Google as having originated in France. A case that, considering that the due tax will be calculated based on the yearly VAT reports submitted to French authorities, is highly unlikely. Without more structural reforms of taxation regimes in fact, applicable tools characterization of income and linkage of digital revenue sources to one jurisdiction would remain largely insufficient to legally pin down owed tax. And needless to say, Google is unlikely to voluntarily start declaring the totality of its income in a 31% CIT jurisdiction.

More realistically in fact, the actual impact of the tax would resemble more closely that of the second column, with a constant amount of reported French revenues. The ineffectiveness of the tax here is even clearer: far from a deus ex machina solution, the net fiscal impact of the DST is of 7.3 million EUR for a subsidiary we can realistically estimate to be earning 3708.6 million EUR a year in revenues.

Digital services taxes: an insufficient solution across the board

While this rapid overview is by no means exhaustive, it is sufficient to get a glimpse of why unilateral initiatives to solve tax avoidance fall short of the mark. The issues start from the point of applicability: from the distortionary effects of gross revenue-based taxation, to the incompatibility with long-established international taxation principles, all the way to the seemingly unfair targeting of foreign companies and the plausible contrasts with privacy regulation. They end with concerns of effectiveness and efficiency. Among the further concerns marring the viability of such taxes, we can note the minor amount of revenue netted, the extensive unintended economic costs, from pass-on costs of the tax to compliance costs and distorted incentives, and finally the significant implementation efforts burdening public administrations.

At best, these initiatives are a catalyst for international talks, a means to flex policy muscles and a bargaining chip at the international negotiating table. Judging by the speed of current OECD negotiations, this view could be dubbed as optimistic. At worst, the French and other DSTs are bound to mainly be a political tool for distraction and short-term gain, rather than the solution they are often portrayed to be.

Real solutions to the tax avoidance and advantageous taxation digital supergroups enjoy can only be international and structural, updating practices of international taxation that have now become obsolete. They cannot be a mere quick fix. Voters demand it, the sustainability of our economic models requires it. Recalcitrant countries, as well as the very groups targeted by these insufficient measures need to understand it: they have got to be talking about taxes. Refusing to sit at the table and stifling progress towards consensus will start not to be enough anymore, as policymakers and citizens start escalating pressure for change. The cost of the proliferation of sub-optimal measures such as the Taxe GAFA risks being massive for all stakeholders involved.

The world deserves better. Structural reform is as urgent as ever. Our faith in the system depends on it. As Bregman himself would put it: “All the rest is bullshit”.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alphabet Inc. ; 2020 ; ‘Alphabet Inc. Fourth Quarter and Fiscal Year 2019 results’ ;

Alphabet Inc.

Alstadsæter et al. ; 2015 ; ‘ Patent Boxes Design, Patents Location and Local R&D’ ; European Commission

Article L64 of the Livre des Procédures Fiscales (2008)

Attac France ; 2019 ; ‘La “taxe GAFA”, une fausse solution à l’évasion fiscale’ ; Attac France ; https://france.attac.org/nos-publications/notes-et-rapports/article/la-taxe-gafa-une-fausse-solution-a-l-evasion-fiscale

Avi-Yonah, R. S. & Xu, H. ; 2019 ; ‘Evaluating BEPS’ ; Erasmus Law Review

Bacache-Beauvallet, M. ; 2018 ; ‘Tax competition, tax coordination, and e-commerce’ ; Journal of Public Economic Theory

Becker, J. & Englisch, J. ; 2018 ; ‘EU Digital Services Tax: A Populist and Flawed Proposal’ ; Kluwer International Tax Blog, http://kluwertaxblog.com/2018/03/16/eu-digital-services-tax-populistflawed-proposal/

Beer, S. et al. ; 2018 ; ‘International Corporate Tax Avoidance: A Review of the Channels, Effect Sizes, and Blind Spots’ ; International Monetary Fund

Bird & Bird ; 2020 ; ‘ Digital Services Tax , Overview of the progress of implementation by EU Member States ‘ ; Bird & Bird

Blanluet, G. ; 2015 ; ‘L’entreprise et la jurisprudence fiscale du Conseil constitutionnel’ ; French Constitutional Council

Bloch, F. and Demange, G. ; 2018 ; ‘Taxation and privacy protection on Internet platforms’ ; Journal of Public Economic Theory

Bourreau, M. et al. ; 2018 ; ‘Taxation of a digital monopoly platform’ ; Journal of Public Economic Theory

Bradshaw, T. ; 2020 ; ‘UK aims to raise £500m a year through digital services tax’ ; Financial Times ; viewed on 16 August 2020 ; https://www.ft.com/content/a2ccbba8-5f0e-11ea-b0ab-339c2307bcd4

Brauner, Y. ; 2014 ; ‘BEPS: An Interim Evaluation’; World Tax Journal

Brauner, Y. and Baez, C. ; 2015; ‘Withholding Taxes in the Service of BEPS Action 1: Address the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy’; IBFD

Brossas ; V. ; 2020 ; ‘Les parts de marché 2020 des moteurs de recherche en France et dans le Monde !’ ; Le PTI Digital ; https://www.leptidigital.fr/webmarketing/seo/parts-marche-moteurs-recherche-france-monde-11049/#Parts-de-marche-des-moteurs-de-recherche-en-France-en-2019

Brynjolfsson, E. and Kahin, L.M. ; 2000 ; ‘Understanding the Digital Economy – Data, Tools, and Research’ ; MIT Press

Canalys ; 2019 ; ‘Canalys: Global cloud market up 37%, with channels creating new growth engine’ ; https://www.canalys.com/newsroom/global-cloud-marketQ32019#:~:text=The%20worldwide%20cloud%20infrastructure%20services,the%20next%20three%20players%20combined

Chamberlain, A. and Fleenor, P. ; 2006 ; ‘Tax Pyramiding: The Economic Consequences Of Gross Receipts Taxes’ ; Tax Foundation

Cobham, A. and Jansky, P. ; 2017 ; ‘Global distribution of revenue loss from tax avoidance’ ; United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research

Cobham, A. and Jansky, P. ; 2018 ; ‘Global distribution of revenue loss from corporate tax avoidance: re‐estimation and country results’ ; Journal of International Development

Cockfield, A. ; 2002 ; ‘The Law and Economics of Digital Taxation: Challenges to Traditional Tax Laws and Principles’ ; International Bureau of Fiscal Documentation

Collier, R. et al ; 2018 ; ‘Dissecting the EU’s Recent Anti-Tax Avoidance Measures: Merits and Problems’ ; European Network for Economic and Fiscal Policy Research

Commercial Court of Paris ; 2020 ; ‘Google France’ ; InfoGreffe ; https://www.infogreffe.com/entreprise-societe/443061841-google-france-750103B094270000.html

Crivelli, E. et al. ; 2015 ; ‘Base Erosion, Profit Shifting and Developing Countries’ ; International Monetary Fund

De Crouy-Chanel, E. ; 2011 ; ‘Le Conseil constitutionnel mobilise-t-il d'autres principes constitutionnels que l'égalité en matière fiscale’; French Constitutional Council ; https://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/nouveaux-cahiers-du-conseil-constitutionnel/le-conseil-constitutionnel-mobilise-t-il-d-autres-principes-constitutionnels-que-l-egalite-en

Deloitte ; 2017 ; ‘BEPS Actions’ ; Deloitte ; viewed on 16 August 2020 ; https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/tax/articles/beps-actions.html

Deloitte ; 2020 ; ‘2020 global survey results on the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) initiative and the next wave of Global Tax Reset’ ; Deloitte

Deloitte; 2016; ‘EU Developments: C(C)CTB and corporate tax Reform’ ; Deloitte

Dischinger, M. and Riedel, N. ; 2011 ; ‘Corporate taxes and the location of intangible assets within multinational firms’; Journal of Public Economics

Dulin, A. ; 2016 ; ‘Les mécanismes d’évitement fiscal, leurs impacts sur le consentement à l’impôt et la cohésion sociale’ ; French Economic, Social and Environmental Council

European Commission ; 2019 ; ‘Data on taxation: statutory tax rates’ ; EU Open Data Portal ; viewed on 16 August 2020 ; https://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/data-on-taxation-statutory-tax-rates/resource/da6b0812-51ac-4d8d-9520-4bbb197d847e

European Commission ; 2019 ; ‘Taxation Trends in the European Union ‘ ; European Commission

European Commission ; 2018 ; ‘Proposal for a Council Directive on the common system of a digital services tax on revenues resulting from the provision of certain digital services. COM/2018/0148 final - 2018/073’ ; EUR Lex

European Commission ; 2020 ; ‘Total general government revenue’ ; Eurostat ; viewed on 16 August 2020 ; https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tec00021/default/table?lang=en

European Parliament ; 2016 ; ‘Tax Challenges in the Digital Economy ; European Parliament

European Parliament Research Service ; 2015 ; ‘Bringing transparency, coordination and convergence to corporate tax policies in the European Union’ ; European Parliament

European Parliamentary Research Service ; 2020 ; ‘Digital taxation State of play and way forward’ ; European Parliament

EY ; 2018 ; ‘Global Tax Policy and Controversy Briefing ‘ ; EY

Faulhaber, L. V. ; 2019 ; ‘Taxing Tech: The Future of Digital Taxation’; Virginia Tax Review

Fleming, S. et al. ; 2020 ; ‘US upends global digital tax plans after pulling out of talks with Europe’ ; Financial Times ; https://www.ft.com/content/1ac26225-c5dc-48fa-84bd-b61e1f4a3d94

Fondation iFRAP ; 2019 ; ‘ Les effets contre-productifs de la «taxe GAFA» ‘ ; Fondation iFRAP ; https://www.ifrap.org/budget-et-fiscalite/les-effets-contre-productifs-de-la-taxe-gafa

Fondazione Nazionale dei Commercialisti ; 2019 ; ‘La tassazione dell’economia digitale. Nota d’aggiornamento.’ ; Fondazione Nazionale dei Commercialisti

French Government ; 2018 ; ‘Livre IS : Impôt sur les sociétés ‘ ; French Government : viewed on 16 August 2020 ; https://www.impots.gouv.fr/portail/www2/precis/precis.html?ancre=cpt-8.5.1.5

French Government ; 2019 ; ‘Lutte contre l’évasion et la fraude fiscales’ ; French Government

French Government ; 2020 ; ‘Impôt sur les societés’ ; French Government ; viewed on 16 August 2020 ; https://www.impots.gouv.fr/portail/international-professionnel/impot-sur-les-societes

French Government ; 1968 ; ‘ Convention entre la France et l’Iralnde tendant à éviter les doubles impositions et à prévenir l’évasion fiscale en matière d’impôts sur le revenu’ ; French Government

French National Assembly ; 2019 ; ‘Avis fait au nom de la commission des affaires économiques sur le projet de loi, après engagement de la procédure accélérée, portant création d’une taxe sur les services numériques et modification de la trajectoire de baisse de l’impôt sur les sociétés (n° 1737)‘ ; French National Assembly

French National Assembly ; 2019 ; ‘ Étude d’impact : Projet de loi portant création d’une taxe sur les services numériques et modification de la trajectoire de baisse de l’impôt sur les sociétés’ ; French National Assembly

French National Assembly ; 2019 ; ‘Projet de loi nº 1737 portant création d’une taxe sur les services numériques et modification de la trajectoire de baisse de l’impôt sur les sociétés’ ; French National Assembly

French National Assembly ; 2018 ; ‘Rapport d’information par la commission des finances en conclusion des travaux d’une mission d’information relative à l’évasion fiscale internationale des entreprises’ ; French National Assembly

French National Assembly; 2019 ; ‘Rapport fait au nom de la commission mixte paritaire chargée de proposer un texte sur les dispositions restant en discussion du projet de loi portant création d’une taxe sur les services numériques et modification de la trajectoire de baisse de l’impôt sur les sociétés’ ; French National Assembly

French Senate ; 2018 ; ‘ ‘Rapport fait au nom de la commission des finances sur le projet de loi de finances, adopté par l’assemblée nationale pour 2019’ ; French Senate

French Senate ; 2019 ; ‘Rapport fait au nom de la commission des finances sur le projet de loi, adopté par l’Assemblée Nationale après engagement de la procédure accélérée, portant création d'une taxe sur les services numériques et modification de la trajectoire de baisse de l'impôt sur les sociétés’ ; French Senate

Fuest, C. and Riegel, N. ; 2009 ; ‘Tax evasion, tax avoidance and tax expenditures in developing countries:A review of the literature’ ; Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation

Fuest, C. et al. ; 2013 ; ‘Profit Shifting and ‘Aggressive’ Tax Planning by Multinational Firms: Issues and Options for Reform’ ; ZEW

Fueuerstein , I. ; 2020; ‘La première cuvée de la taxe GAFA a rapporté 350 millions d'euros’ ; Les Échos ; https://www.lesechos.fr/economie-france/budget-fiscalite/350-millions-deuros-de-recettes-pour-la-taxe-gafa-1205423

Fung, S. ; 2017 ; ‘The Questionable Legitimacy of the OECD/G20 BEPS Project’ ; Erasmus Law Review

Geringer , S. ; 2019 ; ‘National digital taxes – Lessons from Europe’ ; South African Journal of Accounting Research

Giles, C. ; 2019 ; ‘OECD proposes global minimum corporate tax rate’ ; Financial Times ; https://www.ft.com/content/f17a406e-021a-11ea-b7bc-f3fa4e77dd47

Gilley E. et al. ; 2020 ; ‘Digital Taxation—Implications For EU Technology Companies ‘ ; Ropes & Gray LLP ; https://www.mondaq.com/unitedstates/tax-authorities/881350/podcast-digital-taxationimplications-for-eu-technology-companies

Goolsbee, A. ; ‘Implications of Electronic Commerce for Fiscal Policy’, in Lehr, W. H and Pupillo, L. M. ; ‘Internet Policy and Economics Challenges and Perspectives’, Dordrecht

Gravelle, J. ; 2013 ; ‘Tax Havens: International Tax Avoidance and Evasion’ ; Congressional Research Service

Hufbauer G. C. and Lu Z. ; 2018 ; ‘The European Union's Proposed Digital Services Tax: A De Facto Tariff’ ; Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE)

Iacob, N. and Simonelli, F. ; 2019 ; ‘Taxing the Digital Economy: Time for Pragmatism’ ; ISPI; viewed on 16 August 2020 ; https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/taxing-digital-economy-time-pragmatism-24196#n1

International Monetary Fund ; 2019 ; ‘World Economic Outlook Database’ ; International Monetary Fund ; viewed on 16 August 2020 ; https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2019/02/weodata/index.aspx

Iqbal, M. ; 2020 ; ‘App Revenue Statistics (2019)’ ; Business of Apps ; viewed on 16 August 2020 ; https://www.businessofapps.com/data/app-revenues/#1

Italian Chamber of Deputies ; 2019 ; ‘ Web Tax ed economia digitale’ ; Italian Chamber of Deputies ; viewed on 16 August 2020 ; https://temi.camera.it/leg18/post/web-tax-ed-economia-digitale.html

Juranek S. et al. ; 2018 ; ‘Transfer Pricing Regulation and Taxation of Royalty Payments’, Journal of Public Economic Theory

Katz, R. ; 2015 ; ‘The Impact of Taxation on the Digital Economy’; International Telecommunication Union

Kimani, E. ; 2018 ; ‘Tax Avoidance: Meaning, History & Rational’ ; SSRN

KPMG ; 2020 ; ‘Corporate tax rates table’ ; KPMG ; https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/services/tax/tax-tools-and-resources/tax-rates-online/corporate-tax-rates-table.html

KPMG; 2020 ; ‘Taxation of the digitalized economy’ ; KPMG

Laye, S. ; 2019; ‘Amazon répercute la «taxe GAFA» sur ses tarifs: pourquoi la taxation française n’est pas efficace’ ; Le Figaro ; viewed on 16 August 2020 ; https://www.lefigaro.fr/vox/economie/amazon-repercute-la-taxe-gafa-sur-ses-tarifs-pourquoi-la-taxation-francaise-n-est-pas-efficace-20190805

Lehr, W. H. and Pupillo, L. M. ; 2009 ; ‘ Internet Policy: A Mix of Old and New Challenges’, in Lehr, W. H and Pupillo, L. M. ; ‘Internet Policy and Economics Challenges and Perspectives’, Dordrecht

Loretz et al. ; 2017 ; ‘Aggressive tax planning indicators’ ; European Commission

Mahjoubi, M. ; 2019 ; ‘Les Hackers de la Fiscalité’ ; Mahjoubi, M.

Maitrot de la Motte, A. ; 2019 ; ‘Chronique Droit fiscal de l’UE - La Commission européenne a présenté deux propositions de directives relatives à l’imposition des entreprises du secteur numérique’ ; Revue trimestrielle de droit européen

Marques, N. ; 2019 ; ‘La taxation française des services numériques, un constat erroné, des effets pervers’ ; Institut Molinari

Meldgaard, H. et al. ; 2015 ; ‘Study on Structures of Aggressive Tax Planning and Indicators’ ; European Commission

Mikesell, J. L. ; 2007 ; ‘Gross Receipts Taxes in State Government Finance: A Review of Their History and Performance ‘; Tax Foundation Background Paper

Mostafavi, S. and Korenbeusser, S. ; 2019 ; ‘A new French tax on digital services’ ; International Tax Report ; https://www.internationaltaxreport.com/corporate-taxes/article137438.ece

OECD ; 2013 ; ‘Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting’ ; OECD

OECD ; 2013 ;‘Addressing Base Erosion and Profit Shifting’ ; OECD

OECD ; 2014 ; ‘Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy’ ; OECD

OECD ; 2018 ; Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim Report 2018’ ; OECD

OECD ; 2019 ; ‘Programme of Work to Develop a Consensus Solution to the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy’ ; OECD

OECD ; 2019 ; ‘Secretariat Proposal for a “Unified Approach” under Pillar One' ; OECD

OECD ; 2020 ; ‘Corporate Tax Statistics Database’ ; OECD ; viewed on 16 August 2020 ; https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/corporate-tax-statistics-database.htm

OECD ; 2020 ; ‘Glossary of tax terms’ ; OECD ; viewed 16 August 2020 ; https://www.oecd.org/ctp/glossaryoftaxterms.htm

OECD ; 2020 ; ‘Statement by the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS on the Two-Pillar Approach to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy’ ; OECD

OECD, 2015 ; ‘Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy – Action 1: 2015 Final Report’ ; OECD

Olbert, M. and Spengel, C. ; 2017 ; ‘International Taxation in the Digital Economy: Challenge Accepted?’ ; World Tax Journal

OpinionWay ; 2019 ; ‘2017-2019 : la transformation politique du vote Macron’ ; Le Figaro

Overesch, M. ; 2016 ; ‘Steuervermeidung multinationaler Unternehmen: Die Befunde der empirischen Forschung’ ; Perspektiven der Wirtschaftspolitik

Park, W.G. ; 2008, ‘International patent protection: 1960–2005’, Research Policy

Pellefigue, J. ; 2019 ; ‘The French Digital Service Tax An Economic Impact Assessment’ ; Taj

Pierre Moscovici ; 2015 ; ‘Action Plan for Fair and Efficient Corporate Taxation – Speaking points of Commissioner Pierre Moscovici’ ; European Commission

PwC ; 2018 ; ‘Economic and Policy Aspects of Digital Services Turnover Taxes: A Literature Review ‘ ; PwC

PwC ; 2018 ; ‘Understanding the ZEW-PwC Report, “Digital Tax Index, 2017”’ ; PwC ; viewed on 16 August 2020; https://www.pwc.com/us/en/press-releases/2018/understanding-the-zew-pwcreport.html#:~:text=In%20summary%2C%20the%20ZEW%2DPwC,by%20the%20%E2%80%9Cdigital%20sector%E2%80%9D

PwC and ZEW ; 2017; ‘Digital Tax Index 2017’ ; PwC

Rees, M. ; 2019 ; ‘Taxe GAFA : la CNIL juge impossible la rétroactivité au 1er janvier 2019’ ; NextInpact ; https://www.nextinpact.com/news/107697-taxe-gafa-cnil-juge-impossible-retroactivite-au-1er-janvier-2019.htm

SensorTower ; 2019 ; ‘Global App Revenue Grew 23% Year-Over-Year Last Quarter to $21.9 Billion’ ; SensorTower ; https://sensortower.com/blog/app-revenue-and-downloads-q3-2019

Shaxson, N. ; 2019 ; ‘Tackling Global Tax Havens ‘ ; International Monetary Fund

SimilarWeb ; 2020 ; ‘Top Websites Ranking. Top sites ranking for all categories in France (July 2020)’ ; SimilarWeb ; https://www.similarweb.com/top-websites/france/

Solsman, J. E. ; 2019 ; ‘YouTube crosses 2 billion viewers a month’ ; CNET ; https://www.cnet.com/news/youtube-crosses-2-billion-viewers-a-month/

Tang, P. and Bussink , H. ; 2017 ; ‘EU Tax Revenue Loss from Google and Facebook’ ; Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists & Democrats in the European Parliament

Testa W. A. and Mattoon R. H. ; 2007 ; ‘Is There a Role for Gross Receipts Taxation?‘ ; National Tax Journal

UK Government ; 2016 ; ‘Tax avoidance: an introduction’ ; UK Government ; https://www.gov.uk/guidance/tax-avoidance-an-introduction

UK Government ; 2020 ; ‘Digital Services Tax’ ; UK Government ; https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/introduction-of-the-digital-services-tax/digital-services-tax

UNCTAD ; 2017 ; ‘The top 100 digital MNEs, World Investment Report 2017 – Chapter IV’ ; UNCTAD

United States Trade Representative ; 2019 ; ‘Report on France’s Digital Services Tax ‘ ; United States Trade Representative

Vicard V. ; 2019 ; ‘L’évitement fiscal des multinationales en France : combien et où ?’ ; CEPII

ZEW; 2016 ; ‘The Impact of Tax Planning on Forward-Looking Effective Tax Rates’ ; European Commission

Nicola Bressan is a public affairs consultant from Italy. Passionate about the thousand ways tech influences society and citizens, his objective is to understand how to leverage digitisation for the greater policy good.

Read More

Watch Our Episodes