Back in 2011, WHO defined mHealth[1] as medical and public health practice supported by mobile devices, such as mobile phones, patient monitoring devices and other wireless devices (WHO 2011). At present, mHealth accounts for a global market size valued at USD 45.7 billion in 2020 with projected annual growth rate of 17.6 % from 2021 to 2028 (G.V. Research 2014). It involves a plethora of “mobile devices with digital sensors, including clothes, sports shoes, wristbands, adhesive patches or bathroom weight scales or mHealth software, such as mobile phone apps” (Hendl et al. 2020). Approximately, over 320.000 health apps are available on all major app stores (Mulder 2019).

mHealth as a force for good

By lifting geographical barriers, enabling global scientific collaboration based on health-related data analysis and scaling health care services at a lower cost reaching rural areas -where physical medical access is a scarce commodity- mHealth exerts a transformative force for global healthcare and medicine (Free et al. 2013).

According to WHO (2018), mHealth applications can inter alia increase access to quality health services thus reducing maternal, child, and neonatal mortality, and decrease premature mortality from noncommunicable diseases (e.g. obesity). Apart from its health-related impact, scholars observe that mHealth consolidates a shift to a rather preventive and more 'patient-centric' focus by empowering individuals with stronger self-awareness or 'self-determination' rendering healthcare egalitarian, participatory and democratic (Burr et al. 2020; Hendl et al. 2020).

'Googlization' of Healthcare

Many key market players have strategically entered the arena of mHealth and biomedical industry benefiting either from massive data processing generated insights or their healthcare and insurance expertise. Apple maintains since 2015 'ResearchKit', an open source platform allowing scientists to analyze health-related data collected by iPhone Apps. In February 2020, Apple and Johnson & Johnson announced a joint study called 'Heartline' to research whether Apple Watch can detect atrial fibrilation (AFib) thus reducing the risk of stroke (Haselton 2020).

Earlier in 2021, Google completed its acquisition of Fitbit, a health/fitness smartwatch provider, after it was approved by the European Commission contingent on commitments on Google’s part including not to use health data for ad targeting, ensuring the right for EEA users to opt-out from the processing of their data shared with other Google services and fairly handling third-party competition within Android (Porter & Statt 2021; European Commission 2020).

In April 2021, AXA, an insurance provider, partnered with Microsoft to provide a digital healthcare platform including in its pilot phase 'a self-assessment tool, teleconsultation and a medical concierge' (AXA 2021). Only just recently, Google announced its partnership with US national hospital chain HCA operating across 2.000 locations in 21 states to develop healthcare algorithms using patient data (Evans 2021). Amazon is also exploring opening pharmacy stores in U.S. (Reuters 2021). Apple CEO Tim Cook emphasized back in 2019 Apple’s societal contribution via eHealth: “If you zoom out into the future, and you look back, and you ask the question, ‘What was Apple’s greatest contribution to mankind?’ It will be about health” (Gurdus 2019).

Their market position renders these actors not only essential facilitators of health research but rather agenda setters with scholars accordingly describing the phenomenon as 'Googlization of Health Research' (Sharon 2018). Characteristically for a disruptive force, mHealth applications also raise ethical, social and political questions at the interface of technology and society. How each issue is framed can influence its scientific analysis reflecting preferences, embedding biases and -inevitably- blindspots (Djeffal 2019).[3]

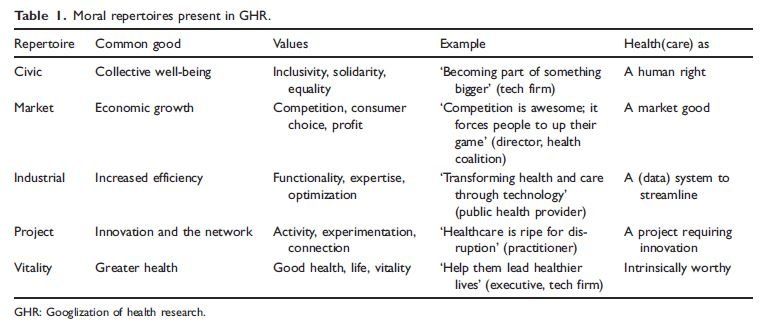

Still these questions should not be approached from limiting dichotomy of public interest versus corporate gain (Sharon 2018). Sharon (2018) draws five different moral repertoires based on constructivist tradition as justifications for the variable vision of the common good (Table I): the civic which approaches the common good as the collective wellbeing connoting notions of solidarity and equality; the market focusing on economic growth and competition, the industrial highlighting efficiency; the project that considers mhealth as an innovative/ disruptive necessary force; and the vitality summarizing narratives propagating the inherent advantages of mhealth as it allows for a healthier population.

Friction between moral repertoires results in ethical, social, political questions (and answers respectively) regarding applications of mhealth.

Ethical challenges

Throughout the evolution of literature regarding ethical aspects of ehealth (Caiani 2021), data protection has unsurprisingly gathered special attention. Due to the sensitive nature of health data collected in private/intimate settings, ethical issues around data ownership, security and consent arise (Burr et al. 2020). Do governments and the private sector comply with data protection rules?[4] How anonymous are anonymized data sets?

Bächle (2019) observes that even in non-profit research environments anonymized data can be re-identified and data security breaches cannot be excluded despite any precautionary measures.

To better understand the challenges around data protection one needs to take a closer look at the concept of purpose limitation. Accordingly, personal data can only be processed for the purpose they were originally collected. Data protection regulations such as the GDPR (Article 9, Recital 35) require a higher threshold for the processing of health-related data. However, all personal data are potentially health-related (Bächle 2019).[5] Especially data transfers have a higher potential for illegal context transgressions, whereby data transcend different contexts and are processed against their original purpose (Sharon 2018).

Against this background, it is reasonable to ask whether data subjects are duly informed when consenting to data processing since at this preliminary stage it is not yet clear what purpose exactly their data will be processed for (Bächle 2019; Mulder 2019; Wild et al. 2019). mHealth also enables the 'transfer of care' from professional healthcare providers to self-monitoring patients with disruptive implications for the traditional doctor-patient relationship. This raises questions of accountability -meaning who should be held accountable for mHealth errors since patients’ autonomous decisions exert a strong influence on any possible outcome?- and of accessibility to digital illiterate populations (Burr et al. 2020).

Scholars also draw attention to possible depersonalizing effects of self-monitoring applications in contrast to their praised potential for stronger patient’s empowerment. The mHealth-promoted constant self-tracking can create unrealistic body, health and lifestyle images that lead to 'higher social pressures, disempowerment, exclusion or decreasing solidarity' among already disenfranchised groups (Ibid.) Intrusive effects in highly personal choices related with nutrition and sexuality can have a harmful impact on mental health, causing 'feelings of bad conscience, guilt, shame', while increasing the risk of depression (Ibid.) Constant performance updates can also be addictive (Ibid.). An increasingly 'quantified' self-perception can create 'data doubles' causing a chasm between our physical and digitally simulated self (Hendl et al. 2020).

Still, disadvantaged groups do not fulfill the socioeconomic conditions (e.g. free time, money) necessary for self-tracking and least self-optimization raising ethical and social questions regarding accessibility (Ibid.). The same problem applies to scoring systems: intuitively a healthy person should get a better insurance deal, but exactly this contradicts the social character of insurance systems based on solidarity (Ibid.).

Surveillance capitalism & digital health

Social challenges also arise out of the discordance between patients’ altruistic motives to provide their health data and companies’ monetization thereof (Sharon 2018). Remunerating patients for their data will lead to a rigid commercialization of eHealth (Bächle 2019). This economic model of 'unexpected and often illegible mechanisms of extraction, commodification, and control that effectively exile persons from their own behavior while producing new markets of behavioral prediction and modification' is defined by Zuboff (2015) as surveillance capitalism.

Algorithms are value-laden embedding discriminatory biases (Hendl et al. 2020; Bächle 2019; Sharon 2018). Thus, gender and racial disparities in the ICT sector are inevitably reflected in the design and content of mHealth applications, e.g., when male developers design woman-focused apps like period trackers or when dating and sex monitoring apps propagate gender stereotypes excluding transgender persons (Hendl et al. 2020).

Disparities in global health policy

Whereas social challenges extend to the political realm, this part only focuses on the political challenges of mHealth on the interface of international relations regarding global health policy with an eye at disparities between developed and developing countries. Germany passed in late 2019 the Digital Health Care Act (Digitale-Versorgung-Gesetz) which -unprecedently for digital health policy- provides for cost reimbursement of approved apps by German statutory health insurance providers (Stern et al. 2020; Gerke et al. 2020).

While mHealth holds great promise for transforming the healthcare sector especially in developing countries, it is exactly these countries that struggle the most to implement global health initiatives due to lack of resources and expertise (Malvey and Slovensky 2017). Health policy makers face critical policy dilemmas 'for such basic life needs as adequate drinkable water and food, and education' that a startup incubator for mhealth may sound luxurious, whereby ICT access is a definitive factor for mHealth potential (Ibid.).

As a result, e-health silos are established between countries that further decelerate the implementation of cross-border mHealth initiatives (Ibid.). Another political challenge is rooted in global competition. Actors like the EU are concerned about policy risks due to the dominant market position of foreign big data corporations (see Madiega 2020) and increasingly weaponize competition rules on grounds of digital sovereignty[6] to assess mergers and acquisitions related with data transfers thereby risking to further demarcate global health policy.

As a disruptive force for good, mhealth holds great promise for global health. However, to stay afloat, we should cautiously navigate around the ethical, social and political challenges in the horizon.

Footnotes

[1] Digital health or ehealth is an umbrella-term referring to the employment of information and communication technologies to deliver health-related[1] information, resources, and services (Bächle and Wernik 2019). Applications of digital health cover a wide spectrum of practice: from telehealth services, health records processing software, interoperability enabling technologies, the most topical tracking of disease and epidemic outbreaks to mobile health (mHealth) including self-tracking devices (WHO 2016).

[2] In the following, I frame arising conflicts according to their addressees and their normative proximity to individual human dignity. Ethical questions aspire to set a moral code for the individual. Under this category fall questions regarding privacy, autonomy, de- or personalization and others related to the “transfer of care” based on the doctor-patient relationship. Questions inherent in the social phenomena framed as surveillance capitalism like data valorization, universal datafication and discriminatory biases fall into the social basket. Issues on the interface of digital sovereignty, international relations, national and global health policy are considered political since they primarily address governance actors.

[3] A 2017 controversy around the data transfer between NHS and Deepmind of 1.6 million patients for the purpose of developing an app that identifies patients at risk of acute kidney injury (AKI) indeed raised data protection concerns, after the Information Commissioner’s Office established a data protection breach due to lack of proper legal basis (Sharon 2018).

[4] Recital 35 GDPR: Personal data concerning health should include all data pertaining to the health status of a data subject which reveal information relating to the past, current or future physical or mental health status of the data subject. This includes information about the natural person collected in the course of the registration for, or the provision of, health care services as referred to in Directive 2011/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council¹ to that natural person; a number, symbol or particular assigned to a natural person to uniquely identify the natural person for health purposes; information derived from the testing or examination of a body part or bodily substance, including from genetic data and biological samples; and any information on, for example, a disease, disability, disease risk, medical history, clinical treatment or the physiological or biomedical state of the data subject independent of its source, for example from a physician or other health professional, a hospital, a medical device or an in vitro diagnostic test.

[5] Floridi (2020) identifies various levels of sovereignty: between states; citizens and the state; citizens and corporations; states and corporations. On the latter level he distinguishes the cybernetic sovereignty of state actors and the poietic sovereignty of corporations. On the EU level, there is a conflict between national and European sovereignty.

References

- AXA 2021. Press release: AXA collaborates with Microsoft to create the next generation standard of health and well-being services: AXA. AXA.com. Available at: https://www.axa.com/en/press/press-releases/axa-collaborates-with-microsoft-to-create-next-gen-health-well-being-services [Accessed May 28, 2021]

- Bächle, T.C., 2019. On the ethical challenges of innovation in eHealth. In: Bächle, T.C. and Wernick, A. 2019. The Futures of E-Health. Social, Ethical and Legal Challenges. Berlin. Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society. [Accessed 27 May 2021].

- Bryman, A., 2007. The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role? International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 10 (1), 5–20 [Accessed 29 May 2021].

- Burr, C., et al. 2020. The Ethics of Digital Well-Being: A Thematic Review. Science and engineering ethics, 26 (4), 2313–2343. Available from: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s11948-020-00175-8.pdf [Accessed 27 May 2021].

- Caiani, E., 2021. Ethics of digital health tools. [online] Available from: https://www.escardio.org/Journals/E-Journal-of-Cardiology-Practice/Volume-18/ethics-of-digital-health-tools [Accessed 27 May 2021].

- Djeffal, C., 2019. AI, Democracy and the Law. In: A. Sudmann, ed. The Democratization of Artificial Intelligence. Net Politics in the Era of Learning Algorithms. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 255–284.

- European Commission, 2020. Press release. Mergers: Commission clears acquisition of Fitbit by Google, subject to conditions. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_2484 [Accessed May 28, 2021].

- Evans, M., 2021. WSJ News Exclusive | Google Strikes Deal With Hospital Chain to Develop Healthcare Algorithms. The Wall Street Journal. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/google-strikes-deal-with-hospital-chain-to-develop-healthcare-algorithms-11622030401 [Accessed May 28, 2021].

- Free, C., et al., 2013. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLoS medicine, 10 (1), e1001362. Available from: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA71/A71_20-en.pdf [Accessed 27 May 2021].

- Floridi, L., 2020. The Fight for Digital Sovereignty: What It Is, and Why It Matters, Especially for the EU. Philosophy & Technology, 33 (3), 369–378.

- Gerke, S., Stern, A.D., and Minssen, T., 2020. Germany's digital health reforms in the COVID-19 era: lessons and opportunities for other countries. NPJ digital medicine, 3, 94. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41746-020-0306-7.pdf [Accessed 27 May 2021].

- Gurdus, L., 2019. Tim Cook: Apple's greatest contribution will be 'about health'. CNBC. Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2019/01/08/tim-cook-teases-new-apple-services-tied-to-health-care.html [Accessed May 28, 2021].

- GV. Research 2014. MHealth Market Analysis and Segment Forecasts to 2020. San Francisco. Grand View Research.

- Haselton, T., 2020. Apple and Johnson & Johnson team up on new study to see if Apple Watch can reduce risk of stroke. CNBC. Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/02/25/apple-and-johnson-johnson-launch-study-to-predict-stroke-risk-with-apple-watch.html [Accessed May 28, 2021].

- Hendl, T., Jansky, B., and Wild, V., 2020. From Design to Data Handling. Why mHealth Needs a Feminist Perspective. In: J. Loh and M. Coeckelbergh, eds. Feminist Philosophy of Technology. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, 77–103.

- Madiega, T. 2020. Towards a more resilient EU. EPRS Ideas Paper. European Parliamentary Research Service. Brussels. European Union. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/651992/EPRS_BRI(2020)651992_EN.pdf [Accessed May 28, 2021].

- Malvey, D.M., Slovensky, D.J. Global mHealth policy arena: status check and future directions. Mhealth. 2017. Sep 22;3:41. doi: 10.21037/mhealth.2017.09.03 . PMID: 29184893 ; PMCID: PMC5682366.

- Mulder, T., 2019. Processing Purposes. In: Bächle, T.C. and Wernick, A. 2019. The Futures of E-Health. Social, Ethical and Legal Challenges. Berlin. Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society. [Accessed 27 May 2021].

- Nissenbaum H. 2010. Privacy in Context. Stanford. Stanford University Press.

- Porter, J. and Statt, N., 2021. Google completes purchase of Fitbit. The Verge. Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2021/1/14/22188428/google-fitbit-acquisition-completed-approved [Accessed May 28, 2021].

- Reuters, 2021. Amazon looking at opening pharmacy stores in U.S. - Insider [online]. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/business/amazon-weighing-entry-into-physical-pharmacy-stores-insider-2021-05-26/ [Accessed 28 May 2021].

- Sharon, T., 2018. When digital health meets digital capitalism, how many common goods are at stake? Big Data & Society, 5 (2), 205395171881903 [Accessed 27 May 2021].

- Stern, A.D., et al., 2020. Want to See the Future of Digital Health Tools? Look to Germany [online]. Harvard Business Review. Available from: https://hbr.org/2020/12/want-to-see-the-future-of-digital-health-tools-look-to-germany [Accessed 27 May 2021].

- Sharon, T., 2018. When digital health meets digital capitalism, how many common goods are at stake? Big Data & Society, 5 (2), 205395171881903 [Accessed 27 May 2021].

- Wild, V., et al., 2019. Ethical, legal and social aspects of mHealth technologies: Navigating the field. In: Bächle, T.C. and Wernick, A. 2019. The Futures of E-Health. Social, Ethical and Legal Challenges. Berlin. Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society. [Accessed 27 May 2021].

- World Health Organization 2021. Global strategy on digital health 2020-2025. Geneva. World Health Organization. Accesible at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/digital-health#tab=tab_1 [Accessed May 28, 2021].

- World Health Organization 2018. Report by the Director-General. mHealth. Use of appropriate digital technologies for public health. Geneva. World Health Organization. Accesible at: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA71/A71_20-en.pdf [Accessed May 28, 2021].

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, op. 2016. From innovation to implementation. EHealth in the WHO European region. Copenhagen: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe.

- World Health Organization 2011. mHealth. Second Global Survey on eHealth. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Zuboff, S. 2015. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs.

Konstantinos Tsakiliotis specialized in Law & Technology at the Humboldt University of Berlin. He provided pro bono service at the Humboldt Internet Law Clinic. He is an alumnus of Harvard CopyrightX and was a judge at the Price Media Law Moot Court in Oxford. He worked at Bundestag and interned at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP. At the Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society, he researched on Global Constitutionalism and the Internet. He founded and currently presides over the Institute for Internet and the Just Society. Konstantinos is interested in digital constitutionalism, deliberative democracy and behavioral game theory especially analyzing irrational actors.

Read More

Watch Our Episodes